Joe Biden: The First Climate Justice President

Contributors: Joseph Galarraga, Dr. Sacoby Wilson, Camryn Edwards

Vice President Biden and Administrator McCarthy at the EPA headquarters by Eric Vance, US EPA

On July 14, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden released policy recommendations centered around environmental justice and economic development entitled “The Biden Plan To Secure Environmental Justice and Equitable Economic Opportunity in a Clean Energy Future”. Vice President Biden tackled a variety of environmental justice issues in his policy proposal, with a focus on an “all government approach” to advancing environmental justice.

With COVID-19 disproportionately affecting Black and Brown communities across the nation, there has been a lot of focus on health disparities and the mechanisms that replicate inequity in the United States. Biden’s plan targets structural inequalities that produce differences in how communities experience climate change and environmental health. The plan also supports further climate and environmental justice research to aid impacted communities. The most important aspects of Biden’s plan focus on emphasizing the role of community leaders and community-based organizations in the fight for environmental justice. Their experiences matter, and they have a right to a seat at the table. Below we will highlight some key elements of Biden’s plan, and recommendations towards more equitable outcomes.

All Government Approach

Biden plans to reallocate resources to establish a new division within the Department of Justice specifically tailored to combatting all issues related to climate and environmental justice. This step comes as a response to large corporations acting as major sources of pollution and facing no repercussions under the current administration. The Environmental and Climate Justice Division would hold these corporations accountable by prosecuting them to the highest extent of the law, including jail sentences.

“South front of the Robert F. Kennedy Department of Justice Building”, by Wikipedia user Baseball Watcher

Biden’s plan also includes the reinvigoration and re-establishment of two environmental groups within the federal government: (1) the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and (2) White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council. These groups will report to the Chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), who will then report directly to the president. These two councils will work with CEQ to support the modernization and revision of Executive Order 12898. This order was enacted with the intention of organizing federal agencies into a collective working group that would target environmental injustices in people of color and low-income populations. It was meant to prioritize people of color and low-income populations by identifying and addressing the disproportionately high human health and environmental effects these communities face as a result of federal agencies’ interference.

With the Trump administration proposing a 26% cut to the EPA and an elimination of 50 of the agency’s programs1, these communities are more vulnerable than ever. When discussing the impacts of environmental justice, the people who will be most affected have to be the center of the conversation. Biden’s plan to revise EO 12898 will hold government agencies accountable to environmental justice communities. Plans for accountability include performance metrics to ensure agencies are carrying out the Executive Order. Additionally, the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council will publish an annual public performance scorecard on the implementation of EO 12898.

To further hold government agencies accountable, Biden outlines his plan for a complete overhaul of the EPA’s External Civil Rights Compliance Office, as it has historically ignored its requirements under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Biden’s plan includes several actions in order to improve Title VI compliance. Biden will revisit and rescind EPA’s decision in Select Steel and its Angelita C. settlement. This ruling made it so that Title VI was subordinate to environmental standards that bear no relation to antidiscrimination law.2 Therefore, this created precedent that civil rights would not be violated unless environmental laws were broken. In the case of this decision, a steel recycling facility was permitted to operate in a predominantly African American neighborhood in Flint, Michigan in 1998.2 Considering the myriad of environmental issues in Flint – especially the city’s water crisis – it must be said that the Select Steel ruling is instrumental in perpetuating a national legacy of environmental injustice.

In order to engage the nation around enforcement of requirements under Title VI, Biden will conduct a rulemaking and open a public comment process to seek Americans’ input on agency guidance for investigating Title VI Administrative complaints. This will improve government transparency and give communities an opportunity to give feedback on how to enforce requirements under Title VI with respect to environmental hazards, ultimately creating standards that reflect the will of the people.

Finally, Biden will work with Congress to empower communities to bring these cases themselves by reinstituting a private right of action to sue Title VI, which was written out in the Supreme Court’s 2001 decision in Alexander v. Sandoval. This action has implications towards community agency, but it should be noted that without community social capital, communities face difficulties regarding self-advocacy and holding forces accountable.3 In order for the private right of action to sue Title VI to truly benefit communities facing environmental injustice, Biden must support local-level coalition building and efforts to create community-level social capital and empowerment.

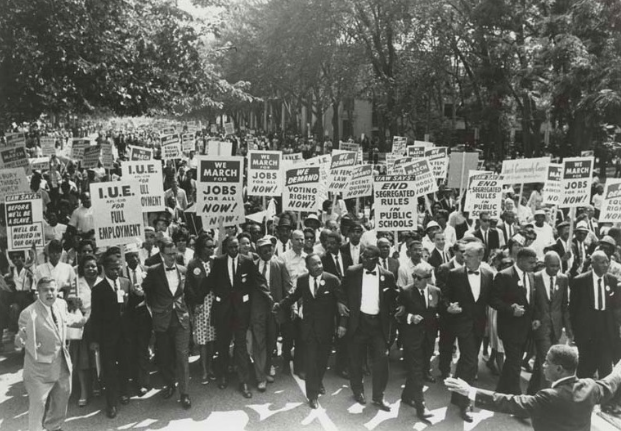

Civil Rights leaders arrive late and link arms in front of marchers on Constitution Avenue, by unknown

Decisions Driven by Data and Science

Biden’s plan highlights the need to make decisions based upon data and science. Within this part of Biden’s plan, the federal government is to increase funding for research databases and technological tools in order to identify communities disproportionately impacted by disasters and environmental injustices. He proposes the nationwide use of a tool, similar to the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Screening tool (EPA EJSCREEN), to produce a map that identifies communities who are experiencing environmental injustice and the multi-source pollution that burdens these populations.

EPA EJSCREEN Tool

While this tool is necessary, it is important to note that each state would benefit from having its own screening tool, rather than relying on a national database. In the state of Maryland, MD EJSCREEN, modeled after the EPA EJSCREEN, has been developed to assist residents in identifying pollution levels in their communities. State-level environmental justice screening tools are necessary because environmental justice occurs at a small scale and require localized data in order to truly uncover the causes of exposure that lead to health disparities.

MD EJSCREEN Tool

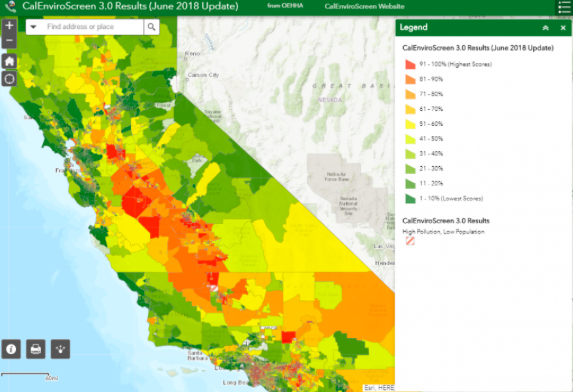

In California, the CalEnviroScreen is used to identify areas that are disproportionately impacted by multiple pollution sources and due to its success, can be used as a model state level tool.

CalEnviroScreen Mapping Tool

While the development of these new tools is a step in the right direction, an emphasis must be placed on hyperlocal monitoring with the data used for enforcement. This means that local monitoring is developed in a way that is both accessible and useful to the community it is assessing. Many communities that are impacted by environmental injustice have had issues with chronic poor air quality. A nationwide study demonstrated that non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics lived in areas with the worst levels of exposure to PM2.5 and ozone.4 A 2016 study in New Jersey found that the risk of dying early from long-term exposure to particle pollution was higher in communities with larger African American populations, lower home values and lower median income.5 EPA regulatory monitors are often not placed in these frontline and fenceline communities which further illustrates the necessity for more site-specific community and neighborhood level air quality monitoring networks.

In a National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) report released on EPA monitoring in 2017, they note that successful community monitoring includes the collection of timely and useful data, accessible and accurate data, is delivered in a way that is most accessible to the affected community, and builds community capacity.6 The Biden plan seemingly recognizes this; Biden advocates for the use of local monitoring and data collection for frontline and fenceline communities. Incorporating this sort of data into environmental justice analysis is crucial to identifying hazards and hazards at the local level. Therefore, performing analyses of these data at the state level through state-specific screening tools, such as MD EJSCREEN and CalEnvironScreen, provides the level of granularity required to ultimately carry out the goals of the Biden plan.

NEJAC Members at the 2016 Meeting in Gulfport, Mississippi, by Karen L. Martin

Map of Hyperlocal Air Pollution and Associated Health Risks (Source: EDF)

The Biden plan also emphasized risk management and disaster preparedness. A NEJAC letter on risk management and the EPA’s Chemical Disaster Rule provides a guideline on eliminating risk in disadvantaged communities. The letter emphasizes the importance of prevention strategies in frontline and fenceline communities and that waiting for a disaster to happen before committing to action constitutes too late of a response.7 Even as recently as this year, explosions in Houston, Texas and Delaware City, Delaware in factories devastated nearby communities because measures were not in place. In the Houston fire immediate structures were torn apart and houses close by were shaken off their foundations.The two fatalities in the explosion were both workers of the manufacturing company. The cause of the Houston fire was linked to a gas leak sparked by an electrical wire at a manufacturing facility, while the Delaware explosion has not been linked to a specific cause.

Biden aims to address these issues with policy that is aligned with Congresswoman Blunt Rochester’s Alerting Localities of Environmental Risks and Threats (ALERT) Act to create a community notification program requiring “industries producing hazardous and toxic chemicals to engage directly with the community where they are located to ensure residents have real-time knowledge of any toxic release and ensure that communities are engaged in the subsequent remediation plan.”

While this policy is a step in the right direction, it does not go far enough. In order for this policy to have its intended effect, the Biden administration must be accountable to impacted communities not only via enforcing the requirements of Title VI and through community involvement in remediation plans, but through stricter regulations on facilities that host hazards in order to avoid future disasters like those seen in Houston and Delaware City. This would best be accomplished via the reinstatement of the complete EPA Chemical Disaster Rule as it stood before Trump’s rollbacks, which includes measures to “prevent accidents, explosions and fires which release toxic chemicals into the air and water.”9

An oil refinery over the west side of Port Arthur, Texas, by Eric Kane

New York Army National Guard Soldiers of the Homeland Response Force for FEMA Region 2 move a simulated casualty to decontamination during an exercise or chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) incident response training, by U.S. Army

Also included as part of the plan to make decisions based upon data and science, Biden also plans to directly fund capacity building, a practice that will allow community leaders to gain more skills and knowledge to allow local grassroots organizations to operate more efficiently and be able to speak with their own voice, one of the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice.10 The “Interagency Climate Equity Task Force to directly work to resolve the most challenging and persistent existing pockets of climate inequity in frontline vulnerable communities and tribal nations.” According to the plan, this includes access to capital and credit for EJ communities.

Biden’s plan towards capacity building addresses several issues related to community capacity and power and certainly is quite progressive, but Biden ought to focus more on “bonding capital” as opposed to “bridging capital.”11 That is to say, instead of planning on merely strengthening the bonds between agencies and communities, the Biden plan should include aims to strengthen the bonds within communities.11 This could be accomplished through good faith efforts to promote equitable community development. Essentially, influxes of capital and resources to communities who are in need of cohesion, opportunity, and salutogenic infrastructure have the potential to miss the mark when it comes to community capacity building.

Data and science will also be brought into the issue of water quality across the United States. To address water quality, Biden intends to set limits for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs) in the Safe Water Drinking Act and test for lead in local drinking water and housing. As of December 2019, limits have not been set for PFAs, but the EPA has implemented a new method for testing PFAs in drinking water.12 These measures would be great strides in ensuring that water is clean and safe for all, considering the pervasiveness of these harmful agents in the U.S. drinking supply.

PFAS Contamination of Drinking Water Across the U.S. (Source: screenshot of the EWG+SSEHRI interactive map via Northeastern University’s Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute)

Recent surveys from the American Water Works Association have also shown that nearly ⅓ of U.S. water systems contained pipelines with lead, with the total number of lead service lines estimated to be near 6 million.13 The most egregious instance of lead contamination in water in recent years can be seen in the community of Flint, Michigan. In 2015, water samples taken from 252 Flint homes showed that lead levels in the water supply had spiked, with over 17% of the samples indicating levels higher than the federal “action” level.14 In September of 2015, a local pediatrician found that blood lead levels in the children of Flint, Michigan had doubled since 2014.14 As of August 20, 2020, the state of Michigan agreed to pay a $600 million settlement to the residents of Flint as a form of compensation.15

Bottled Water Pickup in Flint, Michigan, by USDA

To ensure that the community of Flint and all others like it receive justice, Biden must prioritize replacing piping, especially in areas with old infrastructure. It has been estimated that replacing all lead lines in the country would cost around $30 billion16 – or around 3% of the annual military budget17 or about 15% of Jeff Bezo’s fortune.18 To truly create an equitable plan regarding water quality, the Biden plan must do more. NEJAC released a report in 2018 outlining improvements that can be made to water infrastructure all across the United States.19 The report outlines a number of recommendations, which include: 1) governments treat water as a human right; 2) request Congress to allocate more funding to help communities with infrastructure building, oversight and public health protection; 3) promote affordable water and wastewater rates; 4) prioritize issues in EJ communities 5) involve EJ communities meaningfully in infrastructure decisions; 6) build community capacity in water systems; 7) support innovative technologies; and 8) be accountable and rebuild public confidence and trust in regulations. 19

While Biden’s plan includes provisions that protect water quality and make it affordable, full adoption of the 2018 NEJAC recommendations would go further in ensuring that all water is clean, accessible, affordable, and available in the necessary quantities. Furthermore, it would prioritize the above measures for EJ communities, solidifying his plan as one that centers the experiences of populations who face the brunt of inequity.

Targeting Resources Consistent with the Priority that Environmental and Climate Justice Represent

The Biden plan acknowledges the legacy of environmental injustice in our country, and pledges to invest in low-income communities and community color while undoing legacy pollution. The Biden plan aims to do this by delivering 40% of the overall benefits from green energy investments to EJ communities via “clean energy and energy efficiency deployment; clean transit and transportation; affordable and sustainable housing; training and workforce development; remediation and reduction of legacy pollution; and development of critical clean water infrastructure.”

It is important to note that despite bearing the weight of environmental health hazards in their communities, EJ communities are not responsible for the majority of energy used in this country. According to the NAACP’s “Lights Out in the Cold” report, African Americans are twice as likely to live in poverty as non-African Americans; and spend a higher fraction of their income on electricity and heating compared to non-African Americans, who spend more on energy used in the production and consumption of goods.20 Additionally, the Associated Press reports that, “rich Americans produce nearly 25% more heat-trapping gases than poorer people at home.”21

Biden’s plan to invest green resources into these communities will do wonders to redress some of the injustices that these communities face, but will not necessarily undo the disparities we see in energy bills or energy consumption. To address these issues, Biden should ensure that clean energy be affordable, and that mandatory fees are not dumped upon the communities that use the least amount of energy.22 Additionally, low energy consumption should be further financially incentivized so that low-wealth communities are not subsidizing the energy consumption of their wealthier counterparts. Essentially, while green infrastructure within EJ communities should undoubtedly be supported, Biden’s plan should address the issues associated with energy cost for EJ communities, and the disparities in energy consumption along sociodemographic lines.

Assessing Risks to Communities in Preparation for the Next Public Health Emergency

As the COVID-19 pandemic plagues the nation, the concern for citizens’ health stems beyond the current crisis and raises questions about how future public health emergencies will be handled. The most recent data on COVID-19 cases show that Black and Indigenous Americans face the highest rates of mortality. 1 in 1,125 Black Americans and 1,375 Indigenous Americans have died, whereas 1,2450 White Americans and 1, 2750 Asian Americans have died as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.23 Recent data further indicates that if minority populations had died at the same actual rate as White Americans, 19,500 Black, 8,400 Latinx, 600 Indigenous, and 70 Pacific Islander Americans would still be alive today.23 These numbers are not just for show; they represent actual people and families that have been traumatized by the lack of leadership with respect to fighting the pandemic. Biden plans to greatly decrease the loss of life from disaster and disease through his National Crisis Strategy that addresses climate disasters to prioritize equitable disaster risk reduction and response.

Flooding in Port Arthur from Hurricane Harvey, by South Carolina National Guard

California Wildfires, by Antony Citrano, Climate Change News

The Biden strategy involves allocating resources to disaster risk reduction initiatives and using science-based practices to support states, tribes, and communities that may be disproportionately impacted by climate-related disasters and public health crises. In this plan, Biden again references an “all-government” approach, indicating his eagerness to unify the federal government in the fight for environmental justice. Steps include: 1) creating a National Crisis Strategy to address climate disasters that prioritizes equitable disaster risk reduction and response; 2) Establishing a task force to decrease risk of climate change to children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and the vulnerable; 3) establishing an Office of Climate Change and Health Equity at Health and Human Services (HHS) and launching an Infectious Disease Defense Initiative; and 4) improving the resilience of the nation’s health care system and workers in the face of natural disasters.

To support these initiatives, the Biden plan should also consider the changes made to the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) earlier this year. The Trump CEQ removed language from the proposed rule that placed stricter limits regarding climate change and acknowledged the role of cumulative impacts with respect to environmental health.24 In order to more fully handle the climate crisis, Biden should not only employ mitigation, but make sure that NEPA allows for the review of environmental protections that are tough on climate change and consider cumulative impacts in infrastructure projects.

Based upon our reading of “The Biden Plan To Secure Environmental Justice and Equitable Economic Opportunity in a Clean Energy Future”, the CEEJH lab recommends the following updates and provisions:

Promote coalition-building and the creation of social capital at the community level in order to empower EJ communities to organize and press for enforcement of requirements under Title VI using evidence-based strategies and models.

Follow the lead of states like California and Maryland in the creation of state-level environmental justice screening tools in order to provide communities with data and tools to better advocate for environmental justice.

Incorporate localized data from the monitoring of frontline and fenceline communities into state-level tools in order to produce accurate snapshots of the burdens and hazards that these communities face.

Restore the full EPA Chemical Disaster Rule prior to its gutting by the Trump EPA.

Adopt the NEJAC recommendations for water quality as outlined in the 2018 “EPA’s Role in Addressing the Urgent Water Infrastructure Needs of Environmental Justice Communities” report.

Support energy equity initiatives that consider affordability and energy consumption practices.

Be equitable in the distribution of innovative technologies and strategies to protect EJ communities.

Ensure that NEPA accounts for climate, health, and cumulative impacts for federal actions that affect the human environment.

Center community members’ demands and show compassion/understanding of their experiences in decision making.

References

Beitsch, R., & Frazin, R. (2020). Trump budget slashes EPA funding, environmental programs. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/482352-trump-budget-slashes-funding-for-epa-environmental-programs

The EPA Denies Civil Rights Protection for Communities of Color. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.ejnet.org/ej/tvifactsheet.pdf

Mix, T. L. (2011). Rally the people: building local-environmental justice grassroots coalitions and enhancing social capital*. Sociological Inquiry, 81(2), 174–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2011.00367.x

Christopher, J. P., Martha, H. K., Sharon, E. E., & Marie, L. M. (2011). Making the environmental justice grade: the relative burden of air pollution exposure in the united states. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(6), 1755–1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8061755

Wang, Y., Kloog, I., Coull, B. A., Kosheleva, A., Zanobetti, A., & Schwartz, J. D. (2016). Estimating causal effects of long-term pm2.5 exposure on mortality in new jersey. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(8), 1182–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1409671

Recommendations and Guidance for EPA to Develop Monitoring Programs in Communities. (2017). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-01/documents/monitoring-final-10-6-17.pdf

Re: Recommendation to preserve the Chemical Disaster Safety Rule. (2019). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-08/documents/nejac-recommendations-risk-management-programs-may-3-2019.pdf

Houston explosion: Electrical spark may have triggered blast, ATF says. (2020). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://abc13.com/explosion-watson-houston-cause/5895170/

Gruenberg, M. (2020). Steelworkers sue Trump EPA to save anti-chemical disaster rule. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://peoplesworld.org/article/steelworkers-sue-trump-epa-to-save-anti-chemical-disaster-rule/

The Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/ej-principles.pdf

Chapman, M., & Kirk, K. (2001). Lessons for Community Capacity Building: A Summary of Research Evidence. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from http://docs.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/fulltext/scothomes30.pdf

EPA PFAS Action Plan: Program Update. (2020). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2020-01/documents/pfas_action_plan_feb2020.pdf

Lead in U.S. Drinking Water — SciLine. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.sciline.org/evidence-blog/lead-drinking-water

Flint Water Crisis: Everything You Need to Know. (2018). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.nrdc.org/stories/flint-water-crisis-everything-you-need-know

Schneider, J., & Riess, R. (2020). A $600 million settlement in the Flint water crisis will provide fund for city residents. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/20/us/flint-michigan-water-crisis-settlement-reports/index.html

Replacing all lead water pipes could cost $30 billion. (2016). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.watertechonline.com/home/article/15549954/replacing-all-lead-water-pipes-could-cost-30-billion

Amadeo, K. (2020). Why Military Spending Is More Than You Think It Is. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.thebalance.com/u-s-military-budget-components-challenges-growth-3306320#:~:text=Estimated%20U.S.%20military%20spending%20is,Defense%20alone2%EF%BB%BF%EF%BB%BF

Palmer, A. (2020). Jeff Bezos is now worth more than $200 billion. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/26/amazon-ceo-jeff-bezos-worth-more-than-200-billion.html

EPA’s Role in Addressing the Urgent Water Infrastructure Needs of Environmental Justice Communities (2018). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-05/documents/nejac_white_paper_water-final-3-1-19.pdf

Lights Out in the Cold: Reforming Utility Shut-Off Policies as If Human Rights Matter. (2017). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://naacp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Lights-Out-in-the-Cold_NAACP-ECJP-4.pdf

Borenstein, S. (2020). Rich Americans spew more carbon pollution at home than poor. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://apnews.com/be099434a414a0cb647640ce45f8e6fc

NAACP | Mandatory Fees: Utilities Fight the Future at the Expense of Our Civil Rights. (2015). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.naacp.org/latest/mandatory-fees-utilities-fight-the-future-at-the-expense-of-our-civil-1/

COVID-19 deaths analyzed by race and ethnicity — APM Research Lab. (2020). Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race

Wortzel, A., Levin, A., Cook, A., Smith, B., Little, C., & Sensible, C. et al. (2020). CEQ Final Rule Overhauls NEPA Regulations | Environmental Law & Policy Monitor. Retrieved 28 August 2020, from https://www.environmentallawandpolicy.com/2020/07/ceq-final-rule-overhauls-nepa-regulations/